Like most working-class kids of my generation (I suspect), I grew up convinced that writing in a book – even a book that you owned, and even with a pencil – was a crime that ranked pretty close to murder on the scale of awfulness. My beliefs about writing in books may have been influenced by my mother, who worked in a library. Or they may have been influenced by my experience at a small Catholic school, where everyone knew we would use the same set of classroom books for about one thousand years and must, therefore, tiptoe carefully around and through each book, doing everything in our power to preserve it for the next several generations. “Doing everything in our power to preserve” our textbooks for the next several generations included, of course, not writing in the books.

Naturally, then, I did not write in books. Indeed, I barely interacted with my school books. The textbooks that were assigned to me in high school remained, for most of each year, safely stowed in my locker. I did take each textbook to class with me, placing it neatly on my desk and opening it carefully, if instructed to do so. But that was the extent of my relationship with my high-school textbooks. I don’t recall having taken any of my textbooks home at night, with the exception of my German textbooks. These books were transported respectfully back and forth between the safety of my locker and the precariousness of my desk at home, where they rested dangerously close to the pencil that I used as I practiced grammar and vocabulary exercises on a worksheet from my instructor or a sheet of notepaper. Once, I had been tempted to write in my German One textbook. I had been repeatedly foiled by the word “trotzdem,” whose meaning I could never align with its English equivalent, no matter how hard I tried. Surely, I thought, it would be OK to write the word’s English equivalent in the vocabulary list in the textbook, wouldn’t it? My left hand, with a pencil at the ready, had already begun its descent towards the vocabulary list at the end of the chapter when my moral compass thought better of the whole deal and intervened to stop this small act of book violence.

After this one brief slip, I managed to make it successfully through the remaining three years of my high school studies without once succumbing to the temptation of writing in a book.

And then my college studies happened. More specifically, my college studies in a foreign language happened. I was pretty desperate. All of a sudden, my encounters with the German language had gone from memorizing dialogues about musical groups with unlikely names like “The Hot Dogs” and completing worksheets that allowed me to do what I do best – pull sentences apart, ponder their component elements, and stick them together again in new ways – to the terrifying new experience of reading German literature, discussing (in German, and with people whose German was way better than mine) what we had read, and writing papers (in German) in response to what we had read. To make matters worse, the little yellow paperback literature books that filled the shelves of the university bookstore in the GERMAN LITERATURE section were all set in an impossibly tiny font. To round out the nightmare, the first literature course I took presented German literature chronologically, beginning with the baroque period. While German baroque literature is highly commendable, it’s also largely incomprehensible to a 20th-century American student whose knowledge of modern German spelling and vocabulary are barely sufficient to keep up with a simple news report. Holy smokes.

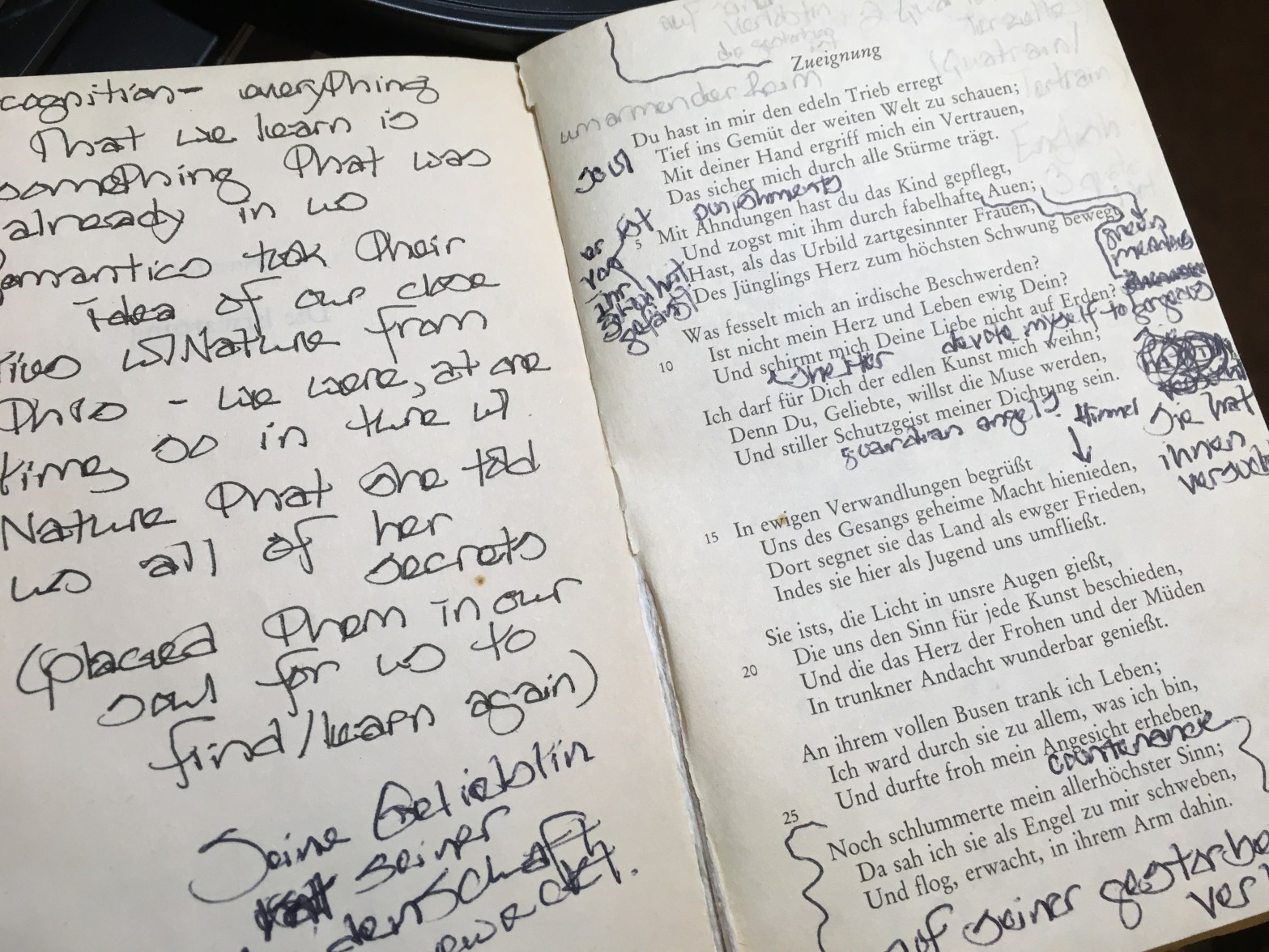

I immediately abandoned my scruples about book violence and began writing – quite liberally – in my literature books. I really didn’t seem to have a choice. In the intervening 20-odd years, I’ve figured out more effective ways of dealing with an overwhelming amount of new vocabulary and complicated sentence structures, but at the time, writing English equivalents of confusing vocabulary items directly on the page seemed like my only option. Pedagogically questionable as the tactic may have been, it did enable me to survive my literature courses. (If you’re curious: I managed to get an “A,” most likely for effort, in each of my German lit courses. Or perhaps my instructors knew that I, being the type of fleißige Studentin who would keep all of those scribbled-in books and read them years later, after having developed sufficient reading proficiency in my second language, would one day gain at least as much cultural and philosophical insight as I was supposed to have gained in their courses. Indeed, the extra years, life experience, and reading fluency that I possessed by the time I read – really read – those scribbled-in books probably offered me a little more cultural and philosophical insight than my instructors had bargained for when selecting those particular works of literature for inclusion on their course syllabi.)

And so I transformed almost overnight into one of “those people” who write in books.

My initial book transgression was perhaps forgivable: I desperately needed those translations to keep up with my coursework. Besides, I wrote them in pencil, and I never sold my books back at the end of the semester, two facts that made my crimes against the printed word seem more tolerable.

But then things got worse. I started writing my translations in pen.

And then things got even worse. I started making margin notes that had nothing to do with language use or the need to translate. I’d jot down ideas or information that had come up in class discussion. I’d pose questions about historical context or seeming inconsistencies in the plot or obscure symbolism. I’d draw arrows or stars around passages that I wanted to remember, so that I could refer to them in my own written work.

Things had descended into utter chaos by the time I entered graduate school after a six-year post-graduation hiatus during which I worked (mostly) as a musician and continued to develop my German reading proficiency by reading every scrap of German text that I could get my hands on and auditing a couple of German literature courses at Lawrence University. By the time I entered graduate school at UW-Madison, I had abandoned all of my writing-in-books inhibitions, writing with great abandon whenever the need arose. I would even go so far as to write notes expressing my disagreement with the author. Things don’t get much worse than writing in a book – with a pen – for the purpose of arguing with the author.

Or maybe that’s not such a heinous act, after all?

As I continued progressing through my graduate studies, I became aware of the concept of “reading like a writer.” The process of reading like a writer is a bit like the process of note-taking, in that it helps the reader take note of those ideas that are most meaningful in her or his own life. It helps the reader reflect on those ideas that are most meaningful in her or his own life. It helps the reader enter into conversation – contentious, agreeable, or somewhere in between – with the writer, even if that writer has been dead for a thousand years. These acts of noting, reflecting, and entering into conversation are vital steps in the writing process, for these are the steps that give a writer “something to say.” These are the acts that help to place a new writer squarely within ongoing conversations about love or fear or war or politics or anything else of special interest to the writer. These are the acts that serve as a springboard for introducing new ideas into ongoing conversations or even for starting a brand new conversation. These are the acts that assure a writer: you have something important and interesting to say.

Writers must build on a foundation not just of reading, but of reading like writers who argue, question, wonder, and explore the things that have gone before. Regrettably, too few of us are taught to read like writers. I, for one, stumbled completely by accident into the practice of reading like a writer, only after having overcome, in a fit of desperation, my conviction that defacing a book with margin notes was tantamount to a capital crime. It’s a wonder I ever learned to read like a writer at all, but this is precisely what happened as my desperate in-text translations turned into conversations with the text, its author, its historical context, my instructor, and my classmates.

While I generally don’t advocate running amok and committing crimes, I wholeheartedly endorse committing the crime of “murder in the book margins,” (i.e. – writing in books, preferably those books that you own and will not sell back to the bookstore at the end of the term). New writers and experienced writers alike will benefit from from this not-so-senseless act of violence against the crisp, pristine margins or between the tidy lines of the printed page. Especially if you find yourself struggling with concerns that you have “nothing to say,” consider shutting down your computer, picking up a pencil or pen, and starting a conversation with your course textbook or a novel or an article that you’ve been assigned to read for class. The conversation is there, waiting for you to dive in. (And yes – it’s OK to dive into the conversation without defacing the book; you can certainly enact your half of the conversation in a notebook or on a piece of scratch paper, but you may find that the authenticity of the conversation is diminished by being physically separated from the author’s contributions to it!)

In the meantime, use the comments section below to share questions about reading like a writer OR to share your favorite strategy for reading like a writer. And tune in next week for more on the idea of writing as a conversation and you, the student writer, as a voice of authority within that conversation!

Happy Reading / Happy Writing,

Dr. Lori